The Ride Linda and I got up about 0530 at the motel. Just after 0600 we walked in the darkness to the next-door restaurant. The only customers inside were an elderly couple at one table and four men at another. The hostess led us to a table next to the four men. I noticed that two of them had shirts that read Skyfire Video or some such. Another had an MRL cap on his head. Seeing these men did nothing to lift my spirits that morning. These were probably the culprits who were bumping me from the 700's cab. I think I scowled at them through most of breakfast.After breakfast we walked back to the motel, checked out, and then drove to the 700. Appropriately we arrived at about 0700. There were less than a half dozen cars parked nearby but the volunteers were everywhere readying the locomotive and the train for the day's journey.

We got out of the car and walked towards the locomotive. It was still dark but the eastern sky was getting light and had some muted colors in it. The mountains that surround Bozeman were a black silhouette against the brightening eastern sky. It was cold. Someone said it was 28 degrees.

As we approached the 700 the number boards and other locomotive lights came on as if to greet us. As we got closer our nearness and the height of the loco combined so its silhouette against the sky replaced that of the mountains. A jet of steam was issuing forth from the turbo generator exhaust on top of the boiler just ahead of the cab. The air pumps were working. Their soft pumping sounds and the slow chuff, chuff, chuff of their exhaust was mingled with the voices of workers getting things ready. With each chuff of the compressors a cloud of steam puffed from the stack. The steam puffs from the pumps and the steam jet from the generator were dark against the lightening sky. Steam that was escaping from other, lower, parts on the dark side of the locomotive appeared white against the black loco.

I quickly found Engineer Jim near the valve gear inspecting his charge. After a short greeting he invited me to an impromptu meeting with the maintenance crew chief, Linda Vanderbeck; the tour planner, and a couple of others who were gathered next to the tender.

The discussion included things such as would they need to take water at Helena? No, Jim thought he could go all the way to Missoula. Linda was asked if mechanically the train would be ready to depart on time? Yes.

A longer discussion was held on how the train would be spotted at Missoula that evening. The track allotted for it near the depot would not hold the entire train. The train would have to be broken up into three pieces to be put on three tracks. The loco with its tenders needed to be near its tool car. All the switches to the three stub tracks faced the wrong way. It was determined the easiest way to handle this would be to stop the train short of the first switch, cut off the 700, and run her into the track nearest the public. Then use the F45 to turn the train on the wye, which leads to the 9th Subdivision. The F45 would then be positioned on the east end of the train where it could shove the cars into the remaining two tracks next to the 700.

Standing there during the discussions I was getting cold. I am somewhat cold blooded and I usually like my cabs a little warmer than my conductors do. It was daylight now but the sun had not yet risen over the mountains. I still did not know if I was going to be riding in the cab or the tool car.

MRL engineer Bob Bateman came up to the group. He was to be our pilot. Bob works an MRL local out of Missoula and spends his weekends running the Alder Gulch steam loco at Virginia City. He had taken it upon himself to work all four of the MRL mainline subdivisions so he would be qualified to accompany the SP&S 700 the entire way. I was introduced to Bob and that was the first time I heard Jim say that I was going to ride in the cab with them today. It seemed to get a lot warmer all at once.

Bob had the MRL "orders" and he discussed them with all of us then passed them to Jim who later passed them to me.

The discussion continued with the subject of roll-by's. The tour wanted three. That was quickly dismissed for lack of time. It would be a long trip and the train had to cross the continental divide. Time would not permit three roll-by's. Maybe they could get two. It was decided to wait and see how the time worked out. The one priority was a roll-by in the canyon between Logan and Toston. This one was desired for the paying passengers so they could take photographs in an area not easily accessible to the throngs of railfans. That way the fans and their vehicles would not be in the passengers' photos. A reasonable request it seemed to me.

The meeting broke up and preparations made for the air brake test. With my ride to Helena assured, my wife left us and if all went well she would meet me in Helena. If not, well, there was always those cell phones.

I followed Jim up into the cab. After the two Billings visits it was becoming a familiar place.

I looked like a dork. Or at least an avid railfan. I had not thought to bring a grip like I take with me to work. I wasn't going to work after all. I was wearing my blue nylon jacket. Over that I had my faded blue denim engineer's coat. I hadn't worn it for years, not since I quit working the helpers. But I thought it might be a good idea on a steam loco to have something over my jacket. I had my 35mm film camera in a big green camera case belted to my waist. My pockets were bulging. I had the cell phone and spare camera batteries in one vest pocket of the coat. The other held my prescription sunglasses. One waist pocket had my Nikon digital camera. The other had a baggie of my wife's oatmeal-raisin cookies, a BNSF blue water bottle, and my own copy of the MRL Timetable & Special Instructions. Most of this stuff was sticking up out of the pocket tops. A small grip would have been a good idea. My regular BNSF leather work gloves were on my hands and my new SP&S 700 cap was on my head.

In the cab I studied my MRL timetable a few minutes and re-read the orders. One temporary slow order about 5 miles west of Bozeman, the siding at Manhattan was blocked with cars, the usual stuff one gets when operating daily on a railroad. Jim had placed the orders on an old worn clipboard. It was the same clipboard his father had used when he worked on the SP&S. The same clipboard his father had carried on the 700 when it was in regular service.

The air brakes were set and the train was walked. Jim checked the brake pipe leakage as required and reported to me, "One P.S.I., pretty good". Bob came up into the cab and told us the dispatcher said there was a broken rail at Lombard.

It was about 20 minutes before our 8am departure when a westbound grain train thundered by on the main. Thinking of that grain train rolling off Bozeman Hill reminded me of the F45's dynamic brakes. I asked Jim if the new potentiometer he had installed in the 700's diesel control box at Billings had operated the F45's dynamic brakes ok coming off the hill yesterday. He said no. He said the diesel transfers into dynamic and even revs up (as older units do) but they got no dynamic braking.

I told him I was worried that if they had used small gauge wire maybe the 150 feet of wiring and the connectors they installed in the tenders and loco may have too much resistance compared to the resistance of the potentiometer (rheostat). If so there would not be enough voltage at the potentiometer's wiper. He said they had used the same size wire as in diesels and of course you have a lot longer wire run on an 8 unit lash up than was on the 700 and her tenders, yet the DB still works on them.

To be sure they were getting the voltage control needed he decided to give me his meter and have Bob and I check it out. We got down and walked past the tenders to the rear of the F45. Bob held up the MU receptacle cover and held a light while I tried to put the meter leads on the proper MU pins. Bob radioed Jim to set up the DB and slowly turn the DB control knob from minimum to maximum. The meter read from 2 volts to 72 volts. That should be good. At least we knew the proper voltage was reaching all the way though the MU lines to the rear of the F45.

I climbed up on the F45 and walked through the engine room to its cab. A couple of Skyfire Video people were working in the cab. I made certain the dynamic brake cut out switch was up and the other control switches were in the proper positions. I figured Jim and Bob knew what they were doing but you never know when something gets bumped or trips. Not being a dash 2, the F45 did not have the motor driven cam switch gear nor its Brake Transfer Control Breaker, which along with its interlocks can sometimes cause DB or power problems. Bob hollered up at me from the ground and threw his grip up to me. I placed it on the cab floor of the F45 then got down and returned to the 700's cab. It was 8am. It was time to go.

Awesome! The morning sun was now streaming in through the cab window. The hand throw switch to the main line was open. The CTC signal just west of the switch showed green over red, Clear. Jim's fireman, Terry Thompson, had the boiler pressure at 260 psi where it was supposed to be. The highball was given and Jim gave two blasts on the whistle. Boy that is no diesel horn! The cylinder cocks were open. He clasped the release on the throttle and pulled the handle back a few inches. Great jets of steam shot out to the sides from the open cylinder cocks. Imperceptibly the great locomotive and its train began to move. There was no slack, no jerk. We just moved.WHUFF! The exhaust erupted. Then almost silence save for some muted hissing of steam. Two, three, four seconds pass. WHUFF! One mile per hour is 1.5 feet per second. It takes 14 seconds for the 77-inch drivers to make one revolution. There are four exhaust blasts for each revolution. That means about four seconds between each exhaust blast. WHUFF! But we don't dally at 1 mph.

WHUFF......WHUFF....WHUFF..WHUFF. Great white plumes of steam are blasted into the sky with each exhaust. The cylinder cocks are now closed and the locomotive is rolling through the switch onto the main line.Jim opens the throttle another two inches. Soon we are at 10 mph and the exhausts come at a rapid 3 per second rate. The sound is a bit sharper and has changed to more of a chuff. Jim is leaning out of the cab window looking back along the train. Chuff chuff chuff chuff chuff chuff chuff chuff chuff chuff. When the last car enters the main he opens the throttle a few more inches, pauses, and then opens it several inches. The locomotive surges ahead. The power increase is instant. Standing next to him I can feel the acceleration pushing me back.

Jim sets the air brakes on the train for the running air brake test. At the same time he moves the independent handle to the left to prevent the driver brakes from applying. After a few seconds the resistance of the train brakes is clearly felt so Jim releases the air.

Now he gets serious and opens the throttle three-quarters full or more. You can feel the power. Feel the acceleration. The locomotive wants to walk out from under you. Twenty-five miles per hour. Soon the back pressure gauge is reading about 25-30 psi. Jim reaches for the power reverse lever and begins hooking up the engine. Thirty. Thirty-five miles per hour. You HEAR the power. It is a continuous roar. Loud! The roar is overlaid with the staccato CH CH CH CH CH CH CH CH of the individual exhausts.

The whistle moans for several crossings.

"Clear block". It is echoed around the cab by three or four of our voices.

Forty-five. Fifty. Fifty five miles per hour and still the acceleration force is there pushing me back. The nearest thing I can think of to describe the noise is its like standing behind a jetliner as it takes off. But it is not the same. There is no hint of jet whine above the roar. Instead you hear the very rapid Tt Tt Tt Tt Tt Tt Tt above it all. It is definitely loud but it is not painful nor does it grate on you the way SD40s do.

"Clear block". Again it is repeated as it will be over and over again throughout the day. For a few miles, while working very little throttle, the exhaust steam was curling down along the right side of the locomotive. In the cold air you could not see through it at all. Every few seconds a clear opening would form allowing us to view the track ahead. Then just as abruptly it would close in again.

Three pairs of eyes were straining to catch a glimpse of the block signals. For maybe 3 or 4 seconds we could see a green signal through a fleeting clearing in the steam. "Clear Block", we all called.

This is awesome. The steam. The roar. The staccato exhaust. The ride. The heat from the backhead. Awesome is the only word I can think of to describe it.

"Yellow flag". This too is repeated throughout the cab. Two miles to the single temporary slow order on our track bulletins. Jim throttles down a bit and lets her settle. He whistles another crossing then sets the air.

The vigilance continues. A whistle post flashes by and the 700's whistle is blown. Half way back along the boiler another green signal appears from the steam and instantly disappears behind us. "Clear Block" we call.

The train is decelerating rapidly. The obscuring steam cloud is now once again up over the locomotive where it belongs and our view ahead is clear. I never see the steam curl down along the side of the locomotive again for the rest of the trip.

Jim releases the brakes and the train speed levels out at 25 mph just as we pass the opposing green flag signifying the beginning of the slow track.

The slow track is a short section and soon the entire train is past the green flag. You can tell that Jim is a passenger engineer. He wastes no time opening the 700's throttle. Raw power is turned loose. The locomotive once again pushes me back. He means to get up to track speed and he means to do it quickly. The 700 does not disappoint, soon we are cruising at 60 mph.

Engineer Jim Abney on the SP&S 700 west of Bozeman, MT

The exhaust is absolutely clear for the first 3 feet or so as it blasts out of the stack. Then it begins to condense in the cold air. It forms a pure white cloud that shoots skyward 10 feet then lays back above the train.

The ride surprises me. I was expecting it would be difficult to stand on my feet at track speed. I expected the steam locomotive to bounce and jerk and lurch its way down the track. I expected vibration and dynamic forces from the piston and connecting rods. But there was none of that. The great Northern rode like a magic carpet. A somewhat stiff magic carpet but sure and steady. There is obviously an advantage in having all those axles. At no time during my four+ hour ride did I ever feel her dive or lurch to one side or bounce vertically the way diesels do. I would say the ride equaled that of an SD40-2, probably the best riding diesel ever built after the E8s. And I mean a new SD40 not one that is totally worn out as they are now.

There is a deck plate that extends out the back of the cab floor and overlays the tender deck. When I was standing in the middle of the cab, or while I was hanging out the left gangway calling signals on that side, I was usually standing with my foot on the edge of that deck plate. It continuously moved about under my foot but only perhaps two inches maximum. It was never wildly jumping about and I had absolutely no problem standing upon it and not holding onto anything even at 60 mph. Anyone who has ridden MU'd diesel locomotives knows that if you look back at your second unit it is frequently bobbing many inches up and down and side to side. There is no such wild gyrations between the Northern and its tender.

We roll west at 60 mph paralleling I-90 where railfans are in hot pursuit. Twenty-five miles west of Bozeman is Logan, MT where the Helena and Butte routes divide. The Butte line is no longer a through route as it has been out of service over Homestake Pass since the late 1980s. The east end of it is still used by a local and by several ballast trains each week which load at Pipestone.

About 4 miles before the junction at Logan Jim throttles down and sets the air brakes. One mile ahead is a 45-mph head end restriction passing a signal due to the grade and the short distance between signals. The signal is Clear. But beginning a short distance beyond it is a permanent 45-mph restriction for the remaining distance to Logan.

Jim sets the air brakes again. At the junction the main line to Helena curves sharply north onto the bridge spanning the Gallatin River and the maximum track speed drops to 25 mph. The 700 and her train rumble across the multispan girder bridge.

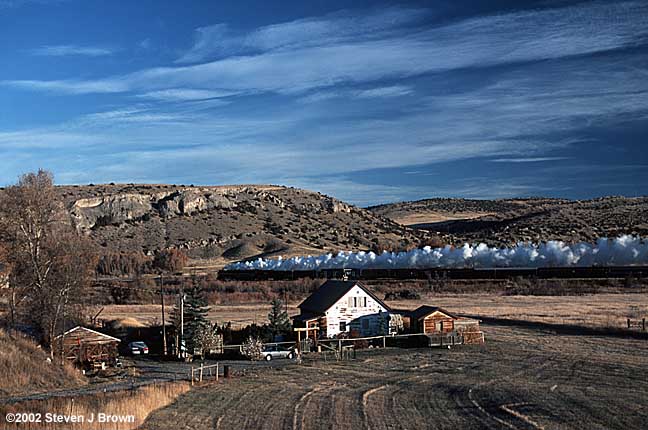

Logan is the point where the Gallatin River, the Madison River, and the Jefferson River combine to form the Missouri River. On the Helena main the next 25 miles of track are in the canyon of the brand new Missouri River. Once clear of the bridge and the first of many curves the track speed increases to 45 mph for a mile then up to 60 mph for three miles. Once again the 700 proves her strength as she bolts ahead quickly accelerating the train up to the limit. The following photo was taken at Logan.

A pair of horses are in a narrow pasture between the railroad and the Missouri. These two horses have to be used to trains passing by. But they are in a full bore linear panic, racing at top speed. They might be used to diesel freights passing but the wailing approach of the steam spouting 700 is too much for them. The Skyfire helicopter pacing us over the river is not helping the horses any either. They are trapped between a hissing roaring monster and a giant bumblebee. I thought they were going to run right through the fence and out in front of us. But at the last second they swerved and raced back along the train.The sixty mile per hour pace does not last long as the airbrakes are set to slow for another 25 mph curve. The nine miles from here to Clarkston is a series of 25, 40, 30, and 45 mph curves.

Engineer Jim Abney on the SP&S 700 between Logan and Clarkston, Montana.

Clarkston is one of only a handful of wide spots in the canyon. It is not on the highway between I-90 and Helena and is accessible only by back roads. The tour operator wanted the 700 and train to perform a run-by for the benefit of the paying passengers. They wanted a photo run-by in the canyon where it would not be cluttered by the many train chasers' vehicles and bodies. But disembarking several hundred passengers, including ladies and elderly patrons, in the rugged canyon presents some problems. Clarkston was chosen as the spot.

Bob, our MRL pilot, contacted the MRL dispatcher to get the required permission and signals for the run-by. He then went to the rear of the train to guide us during the back up moves. Jim had to spot the train three times to position the car doors at a suitable spot for the passengers to disembark. While he operated the 700 I handled the radio chores for him. "Six cars. Two cars. That'll do."

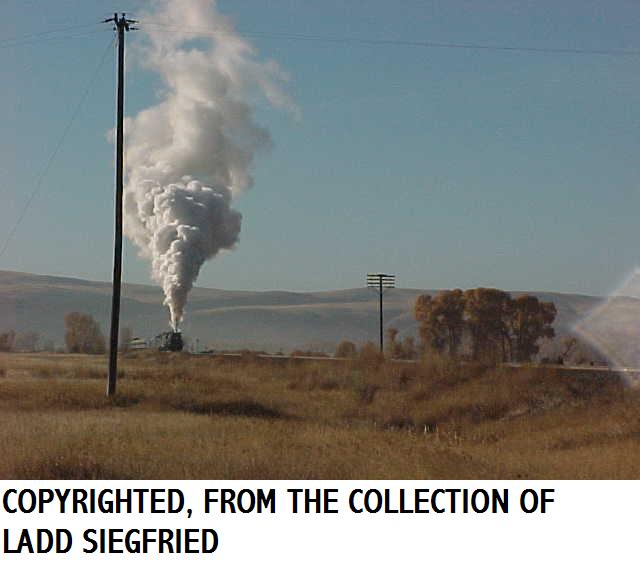

Finally everybody that wanted off was on the ground and the train was backed up a suitable distance and stopped. Terry the fireman had the boiler pressure at 260 psi. Jim was going to put on quite a show. He whistled off and opened the throttle. The 700 and train started to move. He opened the throttle more and the 700 pushed me back. I reached for the edge of the back cab wall. Now Jim had the throttle almost fully open. Terry was controlling the smoke for a clear stack. Steam was blasting from the stack and shooting straight up into the cold air. There it ballooned into a great white roiling cloud ten times as tall as the locomotive. The three miles through Clarkston are good for 60 mph and it looked like Jim was aiming to do it. The locomotive and train accelerated in a thunderous roar, whistle blowing. Wow! It was superb.

The run-by at Clarkston, Montana.

We were just approaching the crowd when I saw Jim suddenly reduced throttle with a look of concern on his face. He shouted to me, "Water carry-over". Sometimes on a steam locomotive if the boiler water level is near the high mark and you are working it at full capacity the bubbly boiling action in the boiler can get so vigorous that bubbles get carried over into the dry pipe. Especially if you get some bad water that likes to foam. The phenomena is much like a pot of potatoes boiling over on your kitchen stove. As you know those bubbles can carry a lot of water over the top of the pan onto the stovetop. On a steam locomotive if that water makes it all the way to the cylinders the hydraulic lock it creates can lift a cylinder head off. Not to worry for the 700 though. Jim had it all under control.He stopped the train and we backed up to pick up the passengers. I asked him how he knew it was working water? He said the first clue was the whistle. He had heard its tone go flat. You could not prove it by me. I had been too busy listening to the glorious stack talk.

Once again he had to spot the train three times to position the car doors for the passengers. Again I handled the radio for him. I was beginning to see why the crew was concerned at that morning's meeting about the time element of making three run-bys. Each one takes the better part of an hour.

After spotting the train for the last group of passengers Jim told me I was going run departing Clarkston. He got down on the ground to do a walk around of the 700. While doing the walk around he found trouble. The bracket that holds the lubricator for one of the air pumps was broken. The lubricator was hanging by the lube lines.

He informed the on-board maintenance crew. Instantly a swarm of maintenance men and women from the tool car appeared carrying ladders and tools. After some inspection and discussion they went to work.

While they were doing that I climbed back into the cab. I grabbed my MRL timetable from my pocket and quickly began studying. From where we were stopped it was 60 mph for about a mile. Then 40 mph for about 1.5 miles then over 9 miles of 25 mph. From there it went to 40 mph for three-quarters of a mile then it was 15 miles of 60 mph into Townsend. Between the sidings of Clarkston and Townsend were Lombard and Toston.

I had never seen this section of track. I had seen the section from Townsend up over Winston Hill to Helena. I knew it was pretty much up and over. Bob had returned from the rear of the train to the locomotive. He asked if I'd like to look at his profile of the track. Yes. Yes I certainly would.

Oh it was worse than I expected. Those nine miles of 25 mph track were a twisted curvy snake. The grade was mostly down but it continuously varied. The track closely followed the Missouri River and every time the Missouri went down some rapids the track also dropped off a bit. When the river leveled out so did the track. But the river was on the fireman's side and would be no help to me. There was no way that I could memorize all those little grade changes and all those curves. I was beginning to see what firemen had to contend with in the days of steam when the old grizzled hoghead said, "You want to run her, boy?"

Not only am I dealing with running a steam engine the first time but I am also dealing with an unknown track and with a trainload of passengers to boot. Running west of Townsend up over the hill instead of west of Clarkston down the river sure looked a lot easier. I mentioned that to Jim and Bob but both of them seemed to want me to run the first section. OK I'm game. I'll take a stab at it.

Using a chain come-along and some blue nylon cargo tie-down straps the maintenance people got the lubricator secured. I believe they turned off the steam supply to the rear air pump so we had only one from there on.

Welding the bracket.About the time the lubricator was secured I heard the dispatcher talking to the section crew at Lombard. They said they had the broken rail back together and were just about ready to give back their Track & Time permit as soon as the ropes burned out. There would be no slow order on it.

| Return to Tales index | My Home Page | E-Mail me |

Created 10-25-2002

Updated 11-20-2002